1960s: Peace, Love, and Polarised Lenses

From Woodstock fields to mod fashion streets, Ray-Ban kept its cool while the world caught fire.

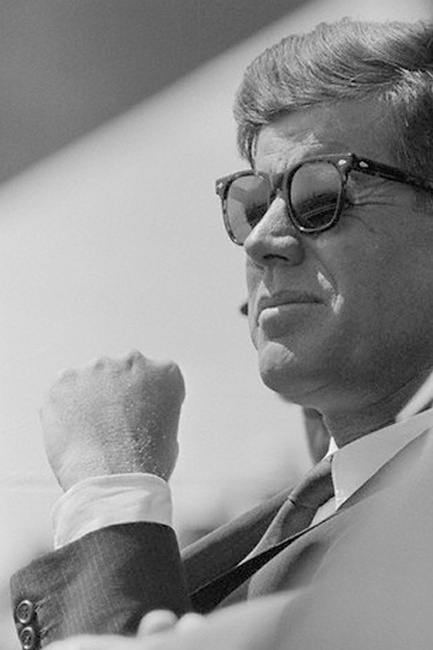

Style Meets Statesmanship

The 1960s were a whirlwind of change, and Ray-Ban kept pace by dramatically expanding its range of styles and technologies. At the dawn of the decade, Ray-Ban already had about 30 models in its catalog; by 1969, it offered over 50 distinct designs . This explosion of variety was no accident – it mirrored the era’s ethos of individual expression. Rather than one or two dominant styles, Ray-Ban introduced sunglasses to suit the many subcultures emerging in the ’60s.

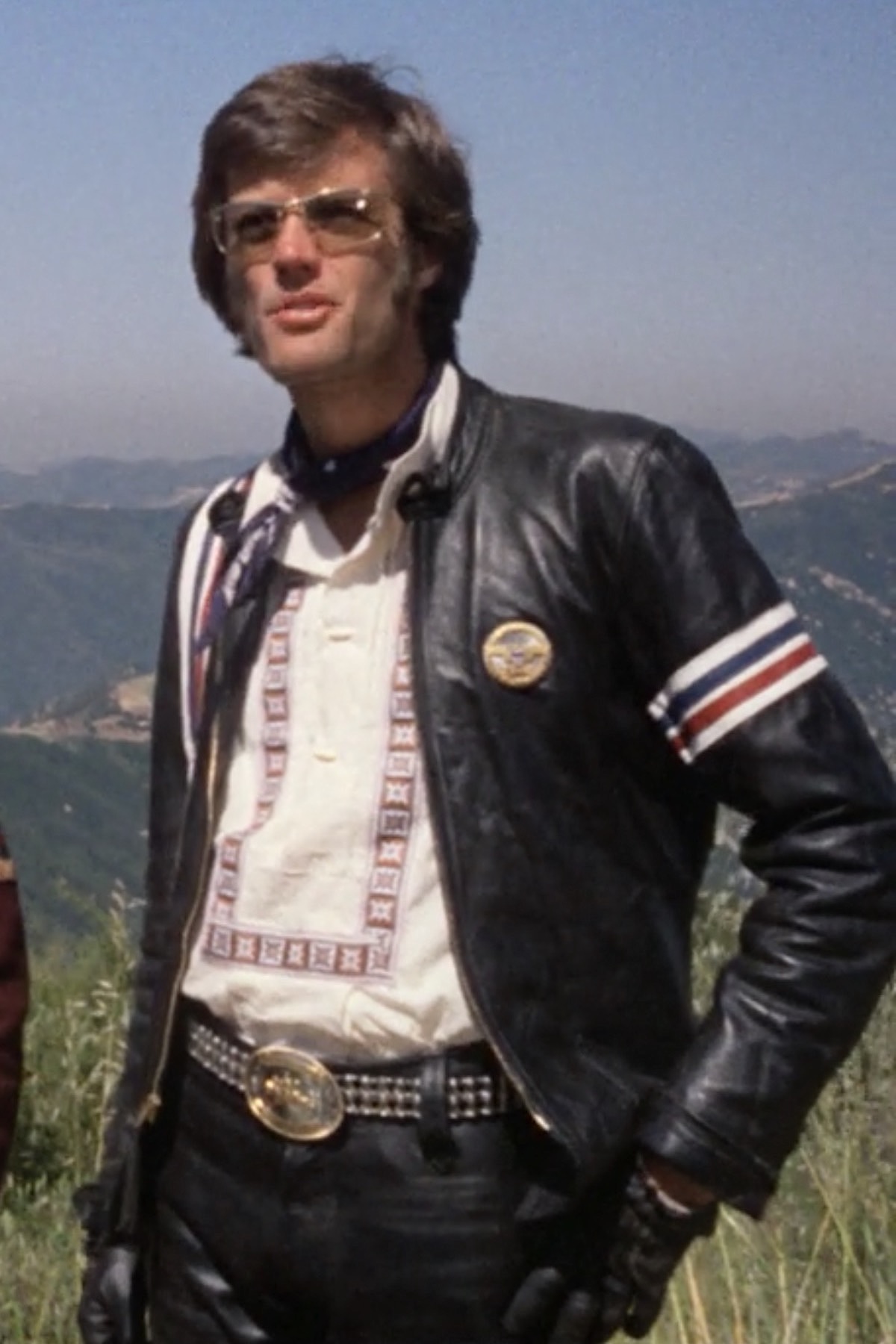

One notable innovation was the Ray-Ban Olympian series. Launched in 1965, the Olympian I and II featured a sleek, continuous metal band across the top of the frames, arching gracefully over slightly curved rectangular lenses . This wraparound design was a departure from both the Aviator and Wayfarer, offering a sportier, speed-inspired look. The Olympian gained massive popularity when actor Peter Fonda wore a pair (the Olympian II) in the 1969 counterculture film Easy Rider . That product placement sent demand soaring – suddenly the youth market saw Ray-Ban not just as their parents’ sunglasses, but as an emblem of the hippie and biker era as well. In a savvy move, Ray-Ban quickly capitalized by highlighting the Olympian in ads, dubbing it the “Easy Rider look,” which only fueled more sales.

Another significant 1960s release was the Ray-Ban Balorama in 1968 . The Balorama was a bold wraparound plastic frame – slightly less boxy than the Wayfarer, with curved edges – designed to hug the face. It exuded a tough-guy vibe that found its way onto none other than Clint Eastwood. Eastwood wore Ray-Ban Baloramas as “Dirty Harry” Callahan in the early 1970s (the film Magnum Force in 1973) , but the model had already debuted in the late ’60s, adding to Ray-Ban’s cred among law enforcement and action aficionados. In the spirit of the space age, Ray-Ban also introduced styles like the Meteor (a chunky plastic frame inspired by the space-race futurism) and the Laramie (a dramatic cat-eye-ish frame) during the decade . Meanwhile, core products got updates: the Aviator saw variant lens colors (like mirrored gold and gradient blue), and the Wayfarer came in new hues and prints to match the psychedelic aesthetic of the late ’60s.

Technologically, Ray-Ban continued to innovate on lenses. In 1962, they rolled out polarized lenses in some models (polarization cuts glare from reflective surfaces – great for driving or fishing). By the mid-60s, anti-reflective and UV coatings were being applied as well, even though such features weren’t heavily marketed until later. Ray-Ban was effectively laying the groundwork to not only be fashionable but also optically superior. By expanding both its design language and its technical prowess, Ray-Ban in the ’60s ensured that it had sunglasses for every face and every scene – from Woodstock to Madison Avenue.

Pop Culture Milestones

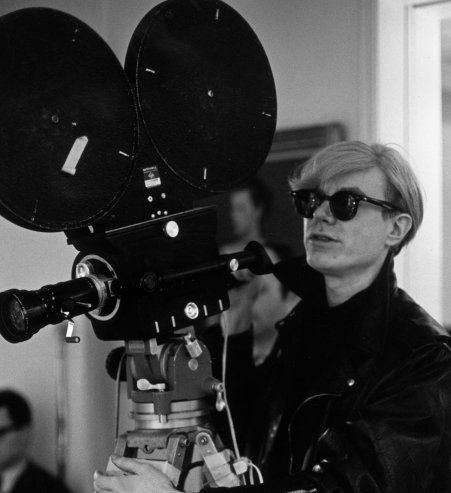

It’s hard to overstate how embedded Ray-Ban was in 1960s pop culture. This was the decade of rock ’n’ roll, of Hollywood’s second golden age, of political movements – and through it all, Ray-Bans were present, shading the eyes of icons in every sphere. The Wayfarer, for instance, transformed from a 1950s movie star accessory into a counterculture badge in the ’60s. Artists like Andy Warhol and bands like The Beatles (George Harrison often donned Wayfarer-style shades) gave the glasses an “indie cool” edge. Bob Dylan became virtually synonymous with his Ray-Ban sunglasses during his peak folk/rock period – on stage and on album covers, Dylan’s mysterious stare from behind dark Wayfarers was an image that epitomized the aloof cool of the ’60s music scene . As one commentator put it, the glasses were as much a part of Dylan’s image as his guitar.

Presidents and political figures also contributed to Ray-Ban lore. As mentioned, JFK sported them in casual settings, and after him, figures like Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. were occasionally photographed wearing classic black sunglasses during marches or outdoor rallies – sometimes Ray-Bans, sometimes similar styles, but the association of “sunglasses = cool leader” only grew. In cinema, Ray-Bans popped up in films beyond Easy Rider. For example, Audrey Hepburn’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s look (though not Ray-Ban brand) had audiences craving big glamorous shades; The Graduate (1967) featured actor Dustin Hoffman in stylish sunglasses in several scenes; and by decade’s end, the idea of a secret agent or detective in shades was a trope (think Bullitt with Steve McQueen, who often wore Persol sunglasses, a trend competitor, but helped the general sunglasses-as-cool factor). Ray-Ban, as the market leader, benefited from all these appearances – whether or not the specific pair on screen was a Ray-Ban, viewers often assumed they were, or went out seeking Ray-Bans to achieve the same look.

One can’t forget the rise of youth counterculture – festivals like Woodstock (1969) and Monterey Pop (1967) saw thousands of young people in fringed clothes, beads, and yes, tinted eyewear. Round “John Lennon” style sunglasses became a hippie staple. While those were often cheaply made copies, Ray-Ban did have a model called the Ray-Ban Round that later capitalized on this trend. Moreover, Ray-Ban’s introduction of colorful lenses and more experimental frames in the late ’60s was a direct nod to the psychedelic movement. They knew that the generation of “flower children” might not go for grandpa’s Aviators, so they offered something new.

By the end of the 1960s, Ray-Ban had managed to stay culturally relevant across the spectrum. Whether you were a biker, a folk singer, a movie star, or a Mod fashionista, there was a pair of Ray-Bans that fit your image. The brand’s sunglasses had become more than just eye protection; they were tools of self-expression. This cultural omnipresence kept Ray-Ban not only in style but also in the public conversation – a crucial factor that would help it endure even as tastes shifted in the coming decade.

Psychedelia and Pop Influence

Ray-Ban’s strategy in the 1960s can be summed up in one word: diversification. Recognizing the rapidly fragmenting market, the brand moved away from a one-size-fits-all approach. Instead, it aimed to have the right product for each demographic and subculture. This meant investing in design (the myriad new styles), expanding marketing channels, and keeping prices accessible yet premium. Ray-Ban sunglasses in the ’60s ranged roughly from $10 to $20 a pair (equivalent to about $90-$180 today), which kept them in the attainable luxury bracket. A college student could save up to buy the same Wayfarers their idol wore, while an executive could splurge on multiple pairs as fashion accessories.

Business-wise, the bet on new styles paid off. The popularity spikes from films (Easy Rider, The Thomas Crown Affair – which featured Faye Dunaway in elegant frames – etc.) translated directly into sales. After Peter Fonda’s Easy Rider appearance in 1969 with the Olympians, Ray-Ban reportedly saw a surge in sales for that model . Similarly, the ongoing demand for Wayfarers and Aviators meant Ray-Ban’s classics remained cash cows. By catering to trendsetters with new designs while still selling the stalwarts, Ray-Ban covered both ends of the market.

The company also expanded its global footprint in the ’60s. With America’s cultural influence peaking, Ray-Ban sunglasses were highly coveted abroad. Bausch & Lomb ramped up exports and licensing deals – for instance, Ray-Bans became popular among European jet-setters and were sold in high-end boutiques in Paris and Rome. The “Made in USA” quality angle was a selling point overseas. This international expansion boosted overall sales volumes significantly.

However, diversifying did carry risks. Maintaining quality across so many models was a challenge, and by the late ’60s Ray-Ban faced competition from fashion brands entering the sunglasses game (e.g. Dior, Gucci licenses for shades). Ray-Ban’s strategy to counter this was to emphasize its heritage and quality – their ads would tout “25 years of scientific research” or similar, quietly reminding consumers that Ray-Ban wasn’t a mere fashion accessory, but a product rooted in expertise . Internally, Bausch & Lomb’s investment in Ray-Ban R&D continued, ensuring the brand didn’t lose its technical edge even as it chased style trends.

By 1969, Ray-Ban’s market performance was strong, but whispers of change were in the air. The Wayfarer, for instance, saw a dip in popularity toward the end of the decade as very different styles (like wire-rimmed granny glasses) came into vogue . Ray-Ban’s broad strategy meant it wasn’t tied to one look, yet the company certainly noticed when one of its flagship models cooled off. Little did they suspect that the Wayfarer would roar back – but that revival would come later. Heading into the 1970s, Ray-Ban had to navigate an even more eclectic style landscape, armed with the lessons and momentum of the swinging sixties.

Marketing & Advertising

1960–1965: In the swinging ’60s, Ray-Ban adjusted its marketing to align with the youthful, rebellious energy of the era. Advertising still touted the classic Aviator and Wayfarer, but with a mod twist: ads featured younger models, sometimes in counterculture fashion (e.g. long hair, casual dress) to appeal to the new generation. Ray-Ban also expanded its product line (offering more lens tints and frame colors), and campaigns highlighted these options with slogans like “Express yourself in Color.” Print media (magazines, billboards) showed rock-and-roll musicians and artists in Ray-Bans, often candid-style photos, implying that creatives naturally gravitate to the brand. This was partly organic – stars like Bob Dylan frequently wore Ray-Ban Wayfarers in the early ’60s, and Ray-Ban’s PR team capitalized on those sightings by circulating the images in press kits . Geographically, Ray-Ban began pushing into the UK and European markets more strongly, using Britain’s rock music invasion as a cultural hook. The messaging tone became a bit more free-spirited: “It’s a Ray-Ban summer” type of copy, linking sunglasses to outdoor music festivals, road trips, and youth freedom.

1966–1969: As the decade progressed, Ray-Ban leaned into sponsorships and event marketing. The brand sponsored high-profile sporting events (like pro tennis and golf tournaments) and music events, ensuring Ray-Ban banners and kiosks were visible – reinforcing the brand’s presence in leisure culture. Advertising by late 1960s also nodded to social movements subtly; for instance, one U.S. print ad circa 1968 depicted a diversity of people (different races and genders) all wearing Ray-Bans with the tagline “The styles may differ, the statement is the same” – positioning Ray-Ban as a unifier of a generation expressing individuality. In terms of creative direction, Ray-Ban maintained its rebellious yet upscale identity. A 1969 Ray-Ban catalog boasted 50 different styles , reflecting how the company’s marketing emphasis had shifted to variety and personalization – “a Ray-Ban for every personality.” Behind the scenes, ad agencies were used regionally (e.g. in Europe, a different firm might handle localized campaigns), but all kept to a consistent visual identity: the Ray-Ban logo and the red label began to be prominently featured. By 1969, Ray-Ban’s sales were at new heights, and the brand enjoyed critical praise for staying cool and current through the turbulent ’60s while never losing its classic appeal.